Preliminary Explorations on UL2 and Second-order Optimizers

In the field of large language models, the most important recipes to cook the model is not opened to publics. Model architecture itself is quite well-known because many state-of-the-art models are now open weights, and in many cases we find it is a boringly simple vanilla transformers.

But for datasets and training objectives it is not well known, and many LLM builders deliberately obfuscates the details of these two. And, of course, these two recipes are much more important than some changes of model architectures.

But how can we know about this important part of recipes? If we cannot expect mere generousity of the LLM makers, then there are no way beside of find out it by ourselves.

It will requires the computing power that individual researchers cannot afford with. But with help of TPU Research Cloud Program (https://sites.research.google/trc/about/) and previous exploration of training LLMs and fancier objectives (OpenMoE, https://github.com/XueFuzhao/OpenMoE), I was able to scratch surface of LLM trainings. I am deeply grateful to both of them.

Fancy Objectives

There are some evidences that leading LLM builders are using fancier objectives beside of plain left-to-right next token predictions. For example PaLM 2 1 mentions they have used “tuned mixture of different pre-training objectives”. Reka models 2 definitely used for encoder-decoder models as they have mentioned sentinel tokens for span masks. Mistral models may have used bidirectional attentions during pretraining, in the form of Prefix LMs. 3

Of course, many code models are trained with non-left-to-right objectives, Fill-In-the-Middle (FIM). 4 But it is for practical applications that needs infilling (i.e., code autocompletes) and does not intend to enhance model capabilities. Actually one of the objective of FIM paper was that incorporating FIM objectives does not harm to general capabilities, not enhancing it.

Fortunately, OpenMoE already explored incorporating new training new objectives in the LLM trainings, by using UL2 5 objectives in the first stage, then continuing the training with vanilla causal language models. As it is common nowadays that using multi-staged training for LLMs, these staged training with changing of training objectives is quite reasonable. But I wanted to try UL2 objectives mixed with causal language models in the form of single stage trainings.

Experiments

Before model training, which is fun part, it is needed to preprocess pretraining corpus. Following OpenMoE I have used mixtures below.

| Dataset | Ratio |

|---|---|

| Common Crawl (2019 Dump only) | 67% |

| C4 | 15% |

| StackExchange | 2% |

| arXiv | 2.5% |

| Wikipedia | 4.5% |

| GitHub | 4.5% |

| The Stack | 20% |

But just downloading and doing some preprocessing like tokenization with these terabytes of data itself it quite hard, and actually impossible if you don’t have enough storages. I was able to do this with TPU instances for TPU Research Cloud, TRC as compute engine. (and persistent disks)

(Yes, maybe it would be better to use SlimPajama instead.)

Then I have adjusted training objectives to simpler than original UL2 objectives. Following 6, which is praised by the author of UL2 (https://x.com/YiTayML/status/1666483764602769408), I have used 60% causal language modeling, 20% prefix language modeling, and 20% span corruption with 2 instances of (noise density, mean noise span length) (0.15, 3), (0.5, 32). And used bidirectional attention mask for prefixes, in constrast of OpenMoE which have used causal masks.

In this scenario, this training objective is quite similar to FIM objectives with prefix lm and bidirectional attention masks.

And I have reduced scaling of training as decreasing number of experts from 32 to 8, and smaller batch sizes with 384 rather than original 1024.

Results

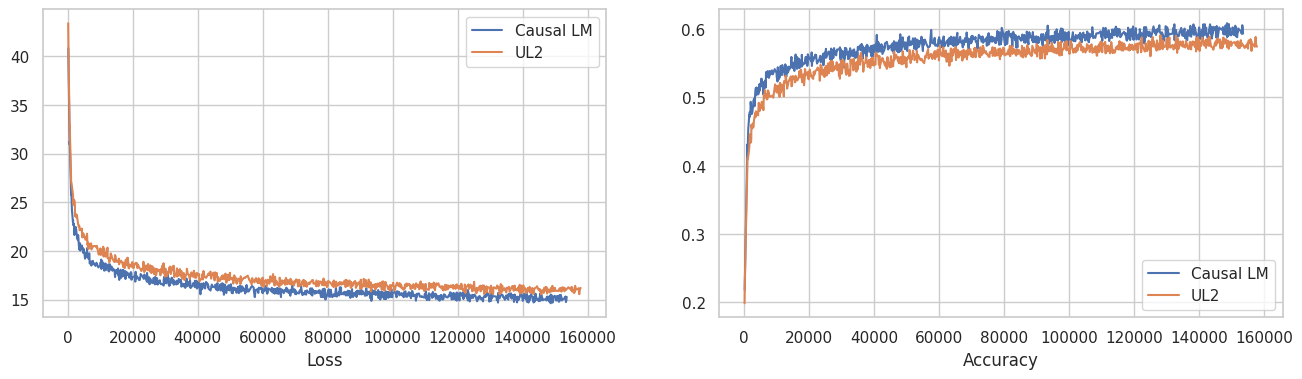

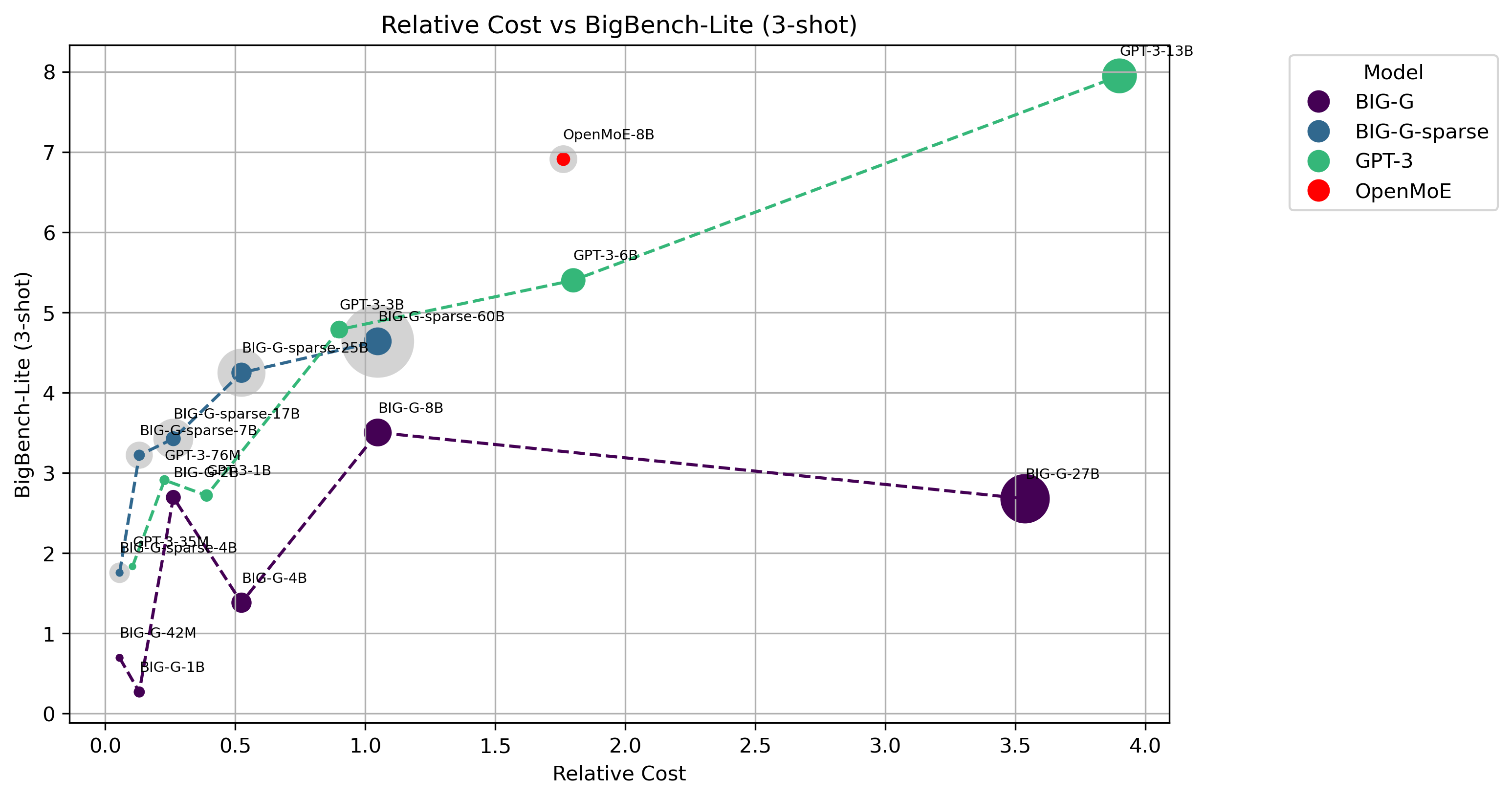

With TPUv4-64 I was able to train model with about 117B tokens. I have evaluated this intermediate checkpoint with BIG-Bench-Lite. I have evaluated UL2 models without bidirectional attention masks.

| Objective | Step | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Causal LM | 145K | 2.65 |

| UL2 | 145K | 3.31 |

| Causal LM | 150K | 3.60 |

| UL2 | 150K | 2.77 |

Score is not high, and definitely oscillating. It maybe because of this is too early stage of the training. I have tried to evaluate these checkpoint with ARC 7 but it just showed chance-level scores.

(https://github.com/XueFuzhao/OpenMoE)

(https://github.com/XueFuzhao/OpenMoE)

It will be not appropriate to derive conclusion from this results. But I think it is possible that UL2 objective is worth exploring, as evaluation scenario (unidirectional causal masking) is pretty different from the training which have used bidirectional attentions. More training steps will allow more concrete prospects.

Higher-order Optimizers.

Rule of thumb for me to evaulating new fancy optimization algorithms is that just don’t belive it. I have tried many optimizers and I was not able to find optimizers that consistently outperforms good old Adam(W). Actually it is quite hard to just find out one cases that newer optimizers clearly outperforms Adam.

Actually there are many researches fancy training algorithms does not outperform just plain, vanilla trainings. 8

There were long history of trying to apply higher-order optimization to deep learning, 9 10 but it is not well-adopted outside optimization researches. I think I found virtually zero cases that higher-order optimization algorithms is used for practical applications in deep learning literatures.

But Gemini 1.5 Flash changed this situation totally. 11 In the technical report Gemini team says that they have used online knowledge distillation and higher-order preconditioned methods for training Gemini 1.5 Flash. It is a powerful evidence that supports using higher-order optimizers to practical applications like pretraining LLMs.

(Actually knowledge distillation also got a power evidences as it was not very popular in LLM trainings after experimentation in Gopher. 12)

So I wanted to find out optimization algorithms that have been used for Gemini 1.5 Flash. I have listed up candidates:

I have decided to test lightweight ones in this list, Sophia and SONew first.

Experiments

I have trained GPT2-Medium and Large on algebraic-stack dataset (https://huggingface.co/datasets/EleutherAI/proof-pile-2) Learning rate is tuned (by hand) and other hyperparameters like β1, β2 are adopted from the literature. Due to memory constraints SONew is not applied to GPT-2 Large.

| Model | Optimizer | Learning Rate | β1 | β2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-2 Medium (355M) | AdamW | 3e-4 | 0.9 | 0.95 |

| GPT-2 Medium (355M) | Sophia | 4e-4 | 0.965 | 0.99 |

| GPT-2 Medium (355M) | SONew | 5e-4 | 0.9 | 0.95 |

| GPT-2 Large (774M) | AdamW | 2e-4 | 0.9 | 0.95 |

| GPT-2 Large (774M) | Sophia | 3e-4 | 0.965 | 0.99 |

Experiments are done using the code from transformers (https://github.com/huggingface/transformers/tree/main/examples/flax/language-modeling) with some modifications.

I found that using BFloat16 can blow-up training, and in addition to float32 softmax in self attention, I need to use more float32 operations in matrix multiplication of attention weights and value matrix.

The author of Sophia suggest that scaling attention by layer index is needed to fully reproduce the results, but I have intentionally dropped this because it would be more common settings. (https://github.com/Liuhong99/Sophia/issues/46#issuecomment-1916215775)

SONew optimizer is implemented in Optax (https://github.com/google-deepmind/optax) following PyTorch implementation of the author. (https://github.com/devvrit/SONew) I found that Optax is one of the most elegant optimizer framework among deep learning frameworks. I have used generous amount of TPUv3-8 instance from TRC.

Results

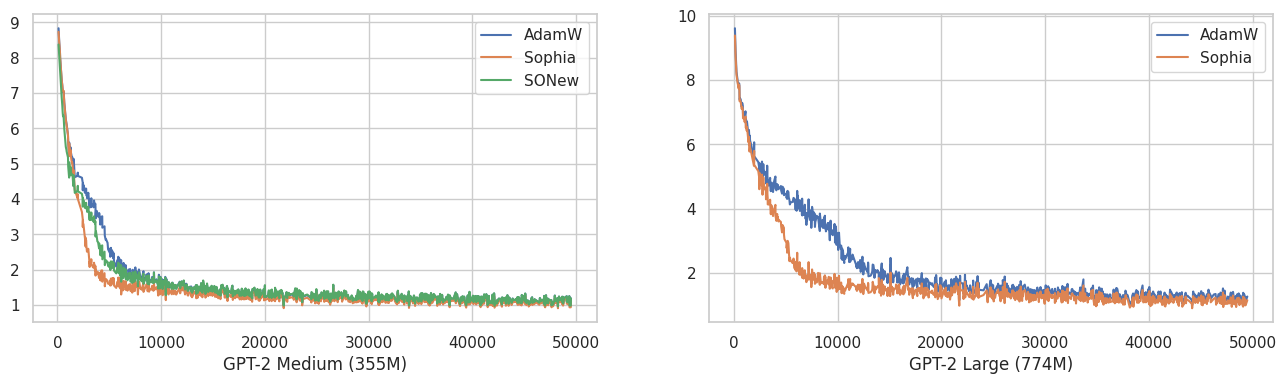

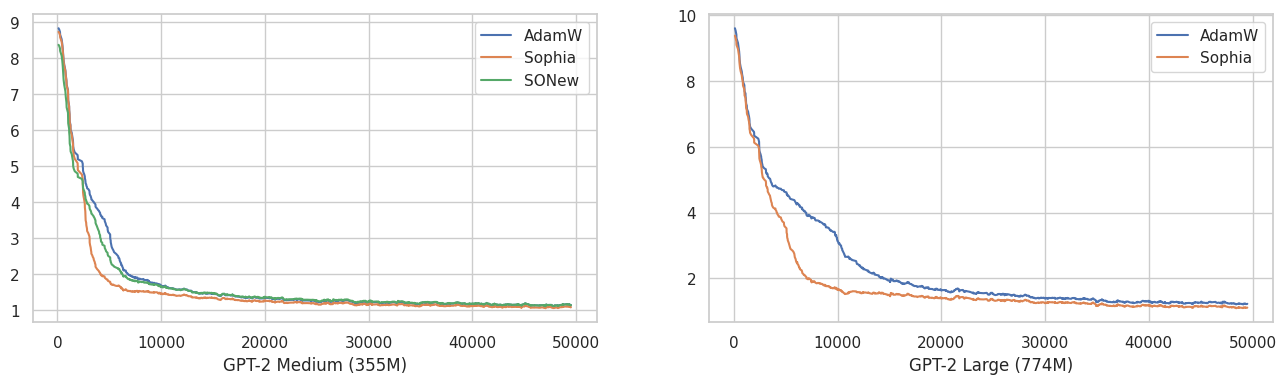

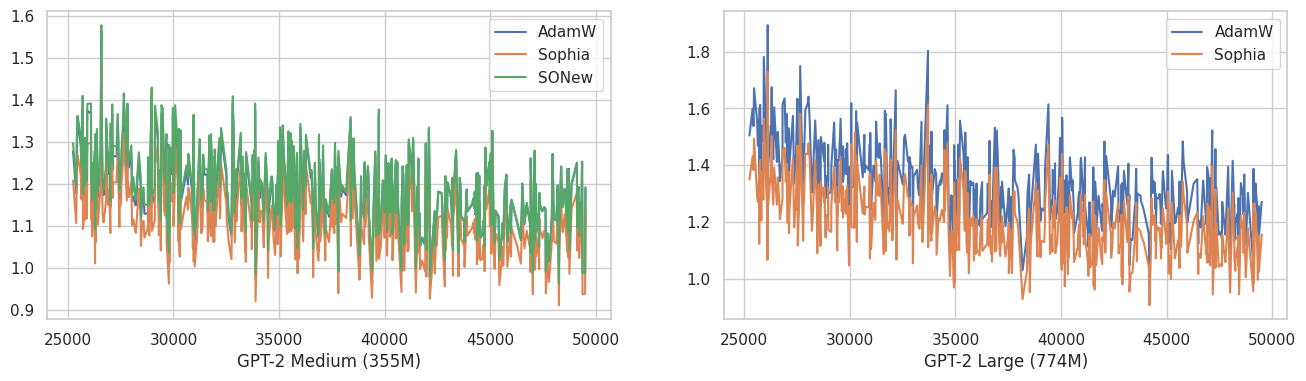

Above is 50K iteration training curve.

This is smoothed version of above with EMA 0.9. If we magnify tail part of training curves,

I found that Sophia optimizer consistently, at least in a small amount, outperforms AdamW. SONew performs about the same with AdamW. Recently Armen Aghajanyan also found that Sophia can outperform AdamW.

(https://x.com/ArmenAgha/status/1777850260829962489)

Of course we need more validations, but as Sophia has about the same runtime with AdamW, it could be worth adopting.

Side notes. There are controversies about implementation of Sophia in Optax (https://github.com/google-deepmind/optax/issues/968) and it is dropped at recent commits. But I found that implementation in Optax is same with the official implementations. (https://github.com/Liuhong99/Sophia)

So What have Google used?

So what optimizer Google have used on Gemini 1.5 Flash? Sophia? But I think it might more fully-featured approximated second-order optimizers like Shampoo or CASPR. But unfotunately I haven’t tried these optimizers yet.

Efficient implementation of second-order optimizers is ongoing research area 16, and as there are powerful evidence of practicality of it, I think we should explore and find out second-order optimizer that could be used for LLM trainings.

Conclusion

In retrospect, I think the objective of exploration of training objects for LLMs was too large to fit in 1 month periods. But, anyway, for me it was useful experiences to run experiments of pretraining LLMs.

Returning to original questions about training objectives, would it beneficial to LLM trainings? Experimentation above does not answer to this, and there are many cases that shows competitive performances with plain causal language modeling, like Llama 3 or DeepSeek V2. So maybe it is not a kind of “crucial” recipes for high-performing LLMs. But again I think some training objective can give you a non-trivial amount benefints. 17 18

For second-order optimizers, I haven’t found what Google have used. Maybe it is especially beneficial in the context of distillation. (https://x.com/arohan/status/1796217021283418351) I think Shampoo or CASPR is promising candidates.

The code that I have used in experimentation is in my GitHub. (https://github.com/rosinality/OpenMoE, https://github.com/rosinality/lm-exp)

About TPUs

This was my first experience with TPUs. Overall it works really well! There was virtually no problem for running experiments. As a small tip, it is better to use nohup to detach the training process from gcloud cli commands, like gcloud alpha compute tpus tpu-vm ssh --command 'nohub train.py &'

Thank you again for TPU Research Cloud. I want to recommend this for everyone who want to run non-trivial sized experiments. Definitely if you well-prepared and organized the experiments before dive into 1 month periods you can get larger amount of results. But it could be blocker for someone to try it, by causing them to think they should be thoroughly prepared before TRC programs. But I think just start the program, and using public resources and codes for TPUs you can do interesting experiments and get a experiences. Anyway doing something after all is better than do nothing worrying about the possibilities of wasting free opportunity.

Anil, R., Dai, A. M., Firat, O., Johnson, M., Lepikhin, D., Passos, A., … & Wu, Y. (2023). Palm 2 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.10403. https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.10403 ↩︎

Ormazabal, A., Zheng, C., d’Autume, C. D. M., Yogatama, D., Fu, D., Ong, D., … & Xie, Z. (2024). Reka Core, Flash, and Edge: A Series of Powerful Multimodal Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.12387. ↩︎

BehnamGhader, P., Adlakha, V., Mosbach, M., Bahdanau, D., Chapados, N., & Reddy, S. (2024). Llm2vec: Large language models are secretly powerful text encoders. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.05961. https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.05961 ↩︎

Bavarian, M., Jun, H., Tezak, N., Schulman, J., McLeavey, C., Tworek, J., & Chen, M. (2022). Efficient training of language models to fill in the middle. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.14255. https://arxiv.org/abs/2207.14255 ↩︎

Tay, Y., Dehghani, M., Tran, V. Q., Garcia, X., Wei, J., Wang, X., … & Metzler, D. (2022). Ul2: Unifying language learning paradigms. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.05131. https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.05131 ↩︎

Garcia, X., Bansal, Y., Cherry, C., Foster, G., Krikun, M., Johnson, M., & Firat, O. (2023, July). The unreasonable effectiveness of few-shot learning for machine translation. In International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 10867-10878). PMLR. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v202/garcia23a.html ↩︎

Clark, P., Cowhey, I., Etzioni, O., Khot, T., Sabharwal, A., Schoenick, C., & Tafjord, O. (2018). Think you have solved question answering? try arc, the ai2 reasoning challenge. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.05457. https://arxiv.org/abs/1803.05457 ↩︎

Kaddour, J., Key, O., Nawrot, P., Minervini, P., & Kusner, M. J. (2024). No train no gain: Revisiting efficient training algorithms for transformer-based language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2023/hash/51f3d6252706100325ddc435ba0ade0e-Abstract-Conference.html ↩︎

Martens, J., & Grosse, R. (2015, June). Optimizing neural networks with kronecker-factored approximate curvature. In International conference on machine learning (pp. 2408-2417). PMLR. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v37/martens15.html ↩︎

Gupta, V., Koren, T., & Singer, Y. (2018, July). Shampoo: Preconditioned stochastic tensor optimization. In International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 1842-1850). PMLR. https://proceedings.mlr.press/v80/gupta18a ↩︎

Reid, M., Savinov, N., Teplyashin, D., Lepikhin, D., Lillicrap, T., Alayrac, J. B., … & Mustafa, B. (2024). Gemini 1.5: Unlocking multimodal understanding across millions of tokens of context. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.05530. https://storage.googleapis.com/deepmind-media/gemini/gemini_v1_5_report.pdf ↩︎

Rae, J. W., Borgeaud, S., Cai, T., Millican, K., Hoffmann, J., Song, F., … & Irving, G. (2021). Scaling language models: Methods, analysis & insights from training gopher. arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.11446. https://arxiv.org/abs/2112.11446 ↩︎

Duvvuri, S. S., Devvrit, F., Anil, R., Hsieh, C. J., & Dhillon, I. S. (2023, October). Combining Axes Preconditioners through Kronecker Approximation for Deep Learning. In The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations. https://openreview.net/forum?id=8j9hz8DVi8 ↩︎

Liu, H., Li, Z., Hall, D., Liang, P., & Ma, T. (2023). Sophia: A scalable stochastic second-order optimizer for language model pre-training. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.14342. https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.14342 ↩︎

Devvrit, F., Duvvuri, S. S., Anil, R., Gupta, V., Hsieh, C. J., & Dhillon, I. (2024). A Computationally Efficient Sparsified Online Newton Method. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36. https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2023/hash/0b43289db08ed60edc6451cb2132e203-Abstract-Conference.html ↩︎

Wang, S., Li, J., Zhou, P., & Huang, H. (2024). 4-bit Shampoo for Memory-Efficient Network Training. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.18144. https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.18144 ↩︎

Bachmann, G., & Nagarajan, V. (2024). The pitfalls of next-token prediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.06963. https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.06963 ↩︎

Gloeckle, F., Idrissi, B. Y., Rozière, B., Lopez-Paz, D., & Synnaeve, G. (2024). Better & faster large language models via multi-token prediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.19737. https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.19737 ↩︎